Posted on

Delivering Ideas

While I worked for Klarna until the company decided to part ways with the 10% of its workforce, I led several key teams within the - so-called Klarna Card, the credit card product offering. What I picked up was in a not so pretty state for reasons I'm not going to discuss here. But, in essence, the teams displayed some clear dysfunctional signs, where the major red flag was the team being reactive.

Reactivity is not necessarily a problem with the team itself or the team members alone, but it's a combination of factors that goes through the whole organisational setup. Leading a reactive team is not something I would ever suggest to anyone starting as a manager, as it requires experience, an excellent analytical approach and more than anything else, support from the leadership. To keep it simple, it comes to three main points:

- Engage with every single individual to make sure there are clear objectives set.

- Understand the workflow to make sure you can create the space needed to address any underlying issues you might discover.

- Engage with the stakeholders to ensure a close loop and transparency on the evolution.

I will keep the first point as a topic for another article and focus on the second point. The third might not need further discussion as it should be part of fostering a culture of transparency and feedback.

I don't expect anything in this article to be new or revolutionary. Instead, the workflow I will describe is something that I consider flexible enough to be used in many environments and can work out of the box without problems and with just a few adjustments.

I have decided to break down this article into three separate sections, ideally allowing anyone to approach this process iteratively and address each stage separately.

I will start from the most obvious step, the development flow, as it will help give guidance and focus to the team.

I will then move into the investigation phase, which will help improve the planning and scope management.

Finally, I will spare a few words on the more product-focus flow, the exploration cycle. Then conclude with a few additional remarks about putting everything together.

Part 1: The agile development flow

This part is likely the most obvious to tackle, probably because most teams will have something like this in place. Furthermore, this whole setup works in an agile environment. I don't specifically adhere to one or the other flavour of Agile, as I like to engage with the team to decide what works best.

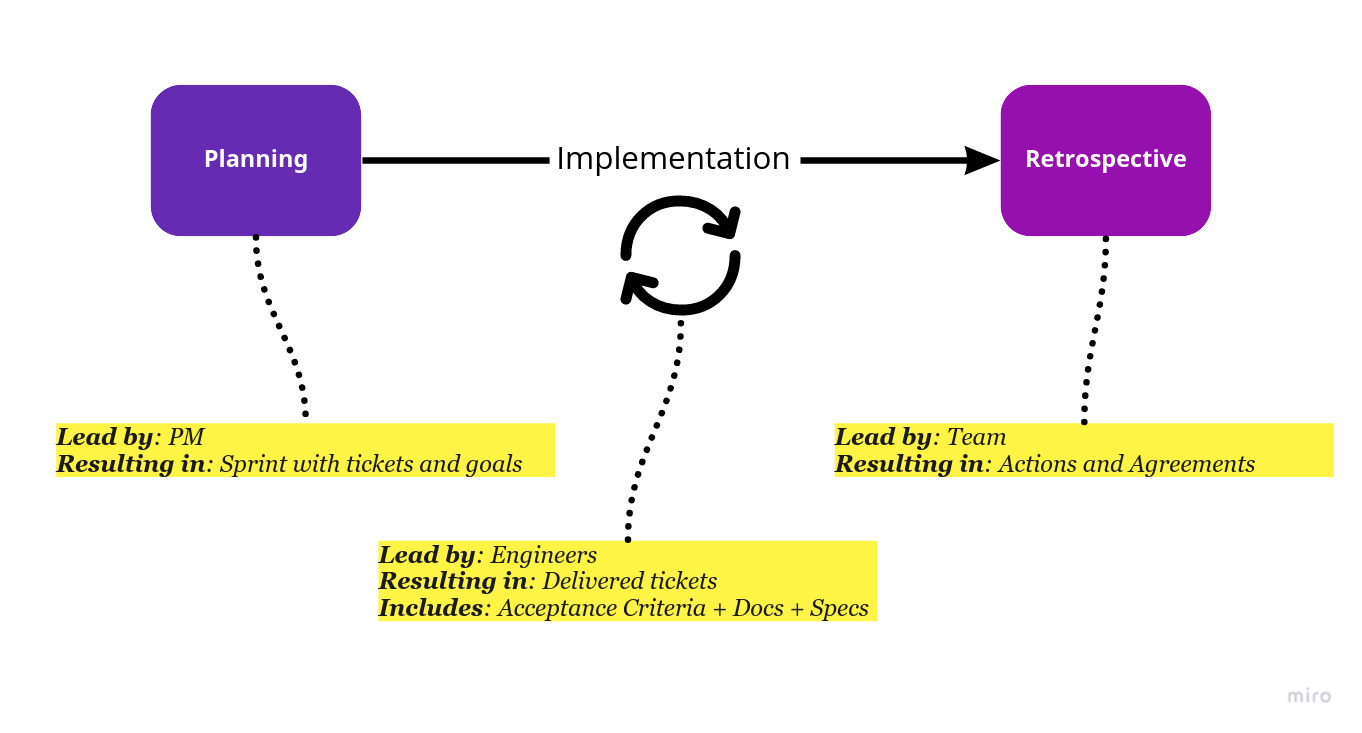

Regardless, everywhere I've been, teams usually use the "Planning - Retrospective" of X weeks cycle (usually 2), with daily standups in between.

If I've just started with a team, I will likely modify the development flow last. So instead, I prefer to collect evidence of patterns and understand if there are causes or symptoms of pain for the team.

Some examples include:

- A messy ticket organisation: e.g. obscure titles, no description in tickets, no definition of done, inconsistent breakdown of tasks, no clear understanding of priorities or the severity of bugs, etc.

- Estimations are just a game you play with cards (if at all): this should require an entirely separate discussion; let me remind you can't predict the future.

- No clear visibility of what's going on at any time: e.g. tickets created during the sprint without precise specifications, and a lot of actual tasks are not even tracked (usually found informally).

- Never-ending tickets or epics: are usually seen as necessary, but there are ways to counter-act this; you want determination and direction on the team's work.

The above might lead you to document everything: this will create a lot of overhead and waste. There is a delicate balance between "getting sh*t done" and "track and control". Generically speaking, and somehow ideally, I would love to have a culture of clear reporting and communication from and between all the team members, essentially aiming at having 100% transparency across the board. If you see that the only way to tackle them means having a documentation-heavy process, so be it, but I warned you.

Two main points I have found to be quite valuable overall:

- Being able to have some metrics: this is extremely useful when it comes to comparing your progress over time.

- Adopt a Kaizen culture: feedback loops cycle are essential to adjust as you go. Ideally, you want small incremental changes rather than extreme ones, as they might screw up any data you have collected so far and force you to start from the beginning.

With the list of dysfunctions at hand, you should start reviewing all the pain points, understand if they're a symptom or a cause, and improve, remove or align the process if there's a lack of consistency.

Between the two checkpoints of the sprint, the idea is to have something along the lines of:

- developers know what they're aiming to get at the end

- there is enough flexibility to address issues along the way

Rinse, and repeat.

Part 2: The feature investigation

Now that you have the engineers engaged in doing what they do best let's talk about what, from what I've seen, most agile environments don't seem to talk about: technical discoveries.

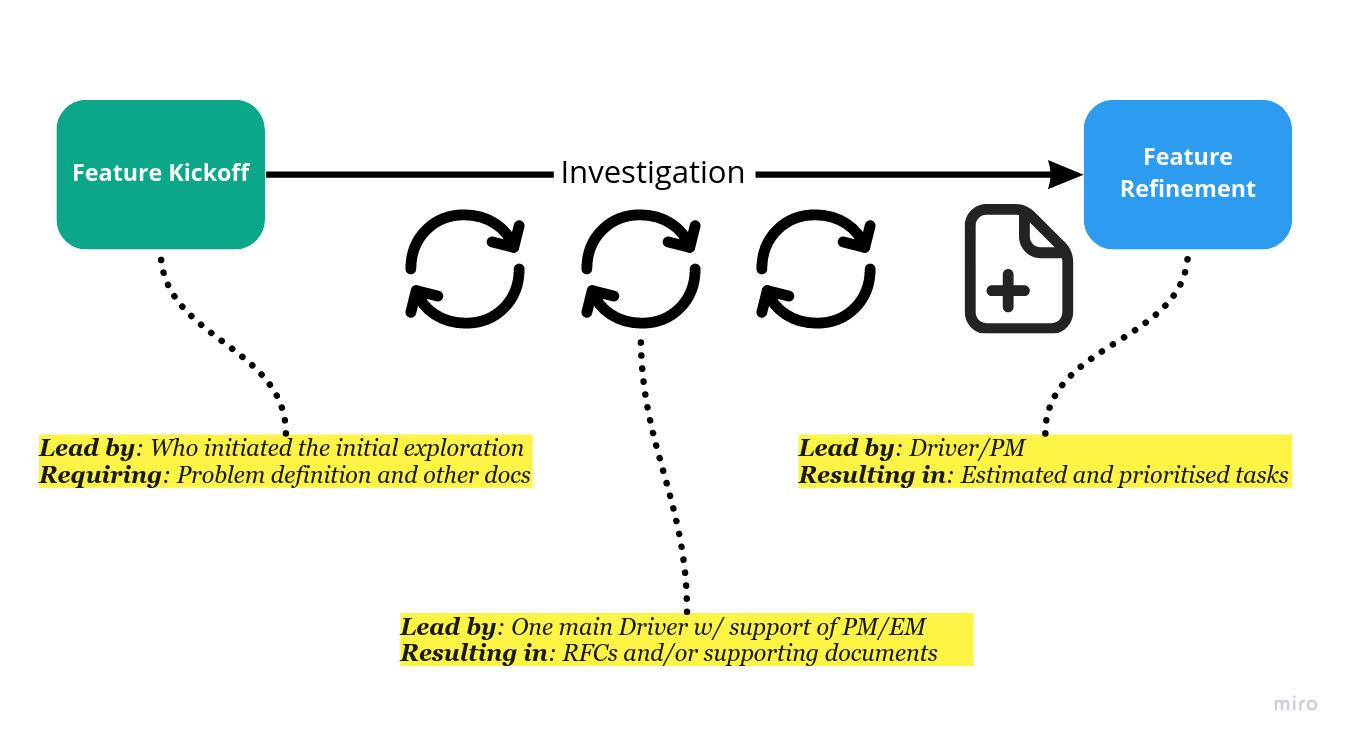

The technical discovery is a cycle that starts with a kickoff meeting, usually with some interested stakeholders that want something to be done but have no idea how to do it. It will eventually end with some refinement meeting, where the team gets together and agrees on the work to do, specifically how it gets broken down.

A few basic rules that worked well in all scenarios:

- Nothing gets kicked off if the development work is not in sight; in other words, let's not waste time if possible.

- The time between refinement and planning should be the shortest but not null. Everyone should be clear that systems evolve so do solutions within these systems. The more you wait, the more likely the whole discovery must be reassessed if not re-done entirely.

In the past, I have faced a spectrum of situations like:

- There is no involvement of the development team at any stage before any refinement or planning session.

- There is only a limited involvement of the development team: selected people get dragged into meetings, leaving one person to work out details and discuss them later during a planning session.

- The constant and seemingly random involvement of the whole team in any new feature discovery; might not be as bad as it looks but has its downsides; most notably, it can cause distractions, if not chaos.

The first two situations are against the transparency principle. They risk isolating team members, creating knowledge silos, and missing opportunities to engage and excite the team to provide the best solution.

I've personally found that there might be a compromise that worked quite well, which led me to introduce the figure of the "driver". The driver is not a one-person band but rather a coordinator who makes sure there is enough documentation, there is only a single source of truth and involves the right people at the right time. Its role ends with the refinement session.

I've seen this role performed by the team lead (if there is one), but introducing it will open up further collaboration and knowledge sharing within the team. Both the Product Manager and the Engineering Manager should have visibility of the current status and help direct and support the process, to avoid creating more complexities.

The refinement session

I need to spend a few words of caution on the feature refinement session.

From a development, product and company perspective, we want to reach our customers as soon as possible, gather feedback used to validate the assumptions, correct any misinterpretations or missing information, and use this information to include it in the next iteration.

Theoretically, having a dedicated refinement session seems helpful in cases where the feature is too complex. Having small checkpoints instead during the discovery phase will help head to a much leaner refinement session, rendering it useless. These sessions will help gather early feedback on the RFC or any PoC created, highlight risks and dependencies, involve specialised external third parties (i.e. architects or domain experts), and define MVP and successive milestones.

On top of that, depending on the amount of stuff that got chucked into the backlog so far, it might be good to have a recurring "refinement" meeting to make sure the backlog is as lean as possible.

Part 3: The feature exploration

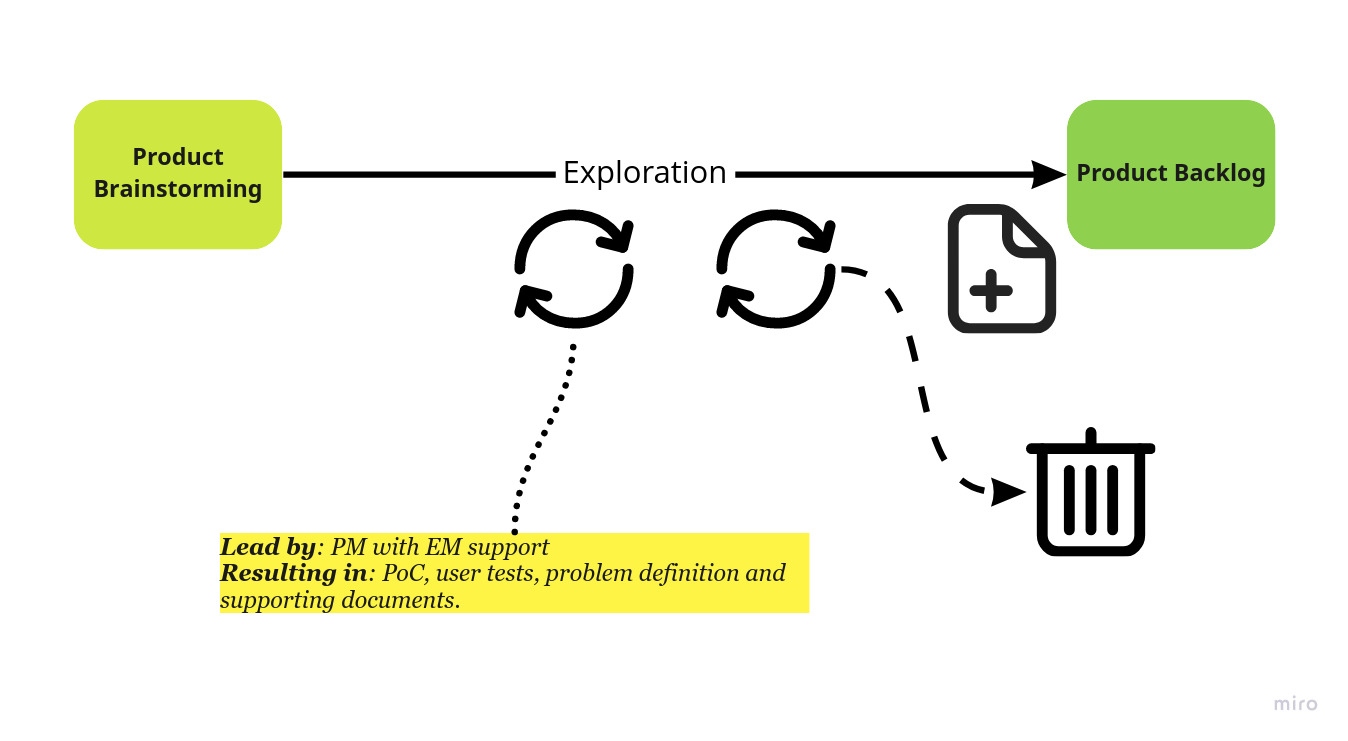

With the above, the team should now be able to assess all the new features coming through the pipeline. Then, the Product and Engineering Manager can focus on prioritisation and effectively move their attention to the most important stuff: product exploration. So naturally, I include anything that affects the product in this exploration phase, e.g. design, UX, analytics, etc.

The exploration phase is perhaps the only area where the Product Manager should have the most significant influence. Their working style and organisational skills should influence how relevant this is and how to organise it. In addition, the relationship between engineering and product should help define how to do it.

I am willingly omitting anything that is not product-related, specifically engineering. As suggested earlier, I try to avoid adding anything to the backlog that is not concrete and has an almost immediate effect on the team's work.

Forcing this approach with the backlog meant I needed to use different informal methods with the rest of the team so that the discussion could flow continuously and leave the door open to improvements of any type. I initiated discussions within the team on how to tackle technical debt, but I'll leave this topic for another article.

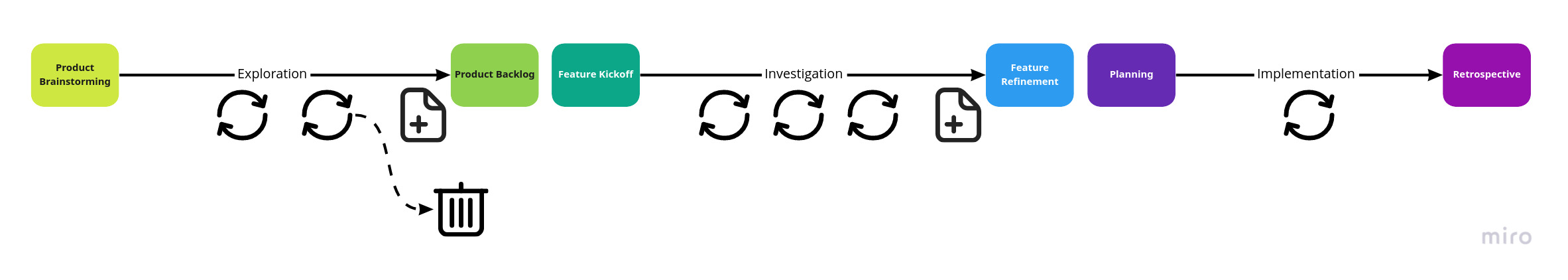

Putting everything together

I hope you managed to stick around until now, and I praise your patience. As I got all of this together, some issues worth pointing out came to light.

As we progressed in formalising our process, we uncovered all the hidden work, meetings, and discussions we had on top of the daily work displayed on the Sprint Board.

This increased visibility allowed the team to decide how much non-dev work to focus on (context-switching is hugely time-consuming ). It also forced leadership to reassess and re-prioritise all the incoming work, leading us to be more impactful in our choices and have clear scope and vision from a team perspective.

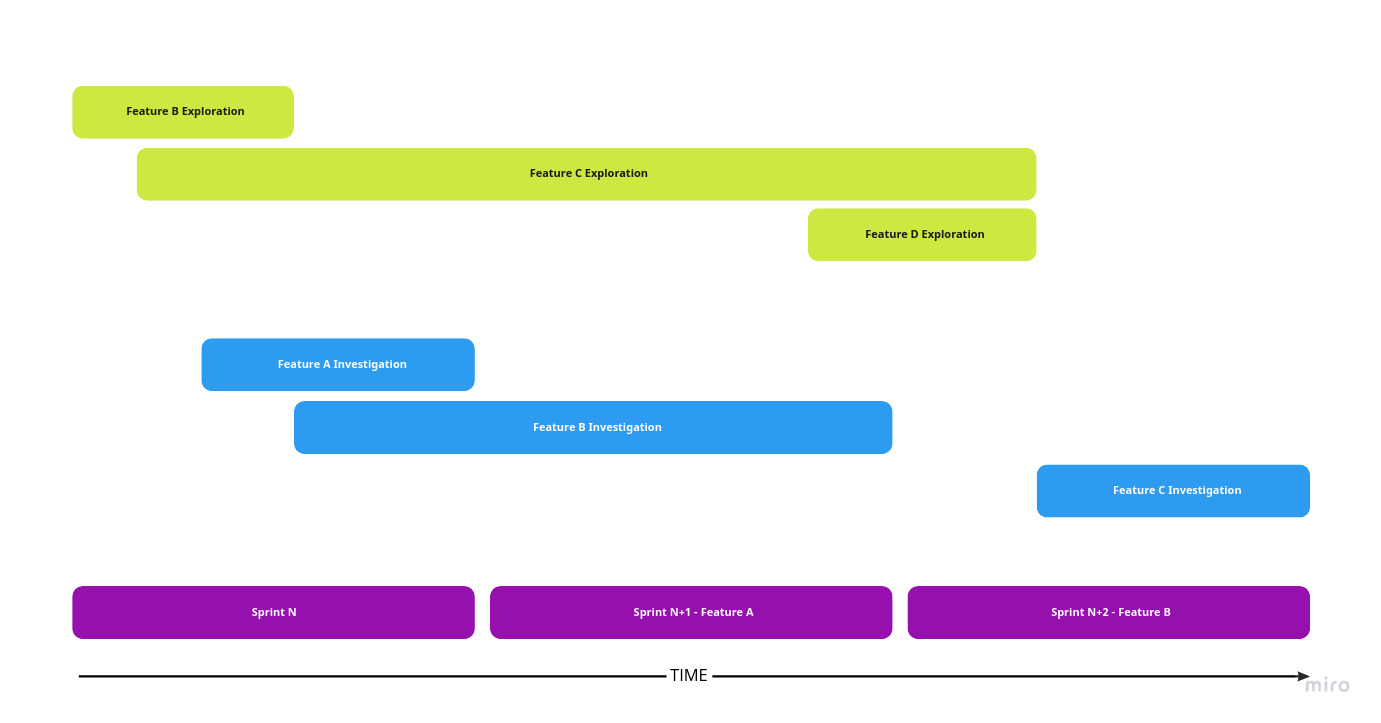

Visualising the Workflow

I found it fundamental to replicate the cycles described above in some workflow software. Moreover, if you can do it with a single software, that would be better as it avoids switching too much and perhaps contains costs.

Klarna's tool of choice is Jira and implementing it was pretty straightforward. And its flexibility allowed me to pick and choose the right processes and automate them as needed.

If you're not familiar with Jira's terminology, suffice to say that Epics are a way to collect "tickets" together. Tickets come in different flavours to help differentiate the type of work, e.g. Stories, Tasks, Spikes, Bugs.

Some of the agreements we had in place helped manage the situation more flexibly:

- Epics represent a self-contained deliverable made of stories and tasks. They can easily convey a milestone (there are other ways to do that in Jira, but this proved to work as needed for our use case).

- Spike ticket types were used for time-boxed investigations and could be used to highlight the work done within the sprint and give the right level of visibility to everyone.

Specifically, I had three main boards representing each cycle described above within the same Jira project.

The first two boards for the Exploration and Investigation cycles used an endless Kanban-style board that displayed Epics exclusively. In contrast, the third one for the implementation cycle was a sprint-based board used daily by everyone.

Conclusion

I strongly recommend anyone getting in similar situations run a "ways of working" workshop to reassess the current process and find improvement opportunities all together.

It's impossible to do this workshop without breaking down how the team currently processes work, which is probably the most challenging task I had to go through in my career. This workflow visualisation exercise is easy enough, as suggested by some Kanban practitioners if you try to map the flow in terms of statuses. The involvement, participation and support of the product manager and even some key stakeholders might also be essential to support the process.